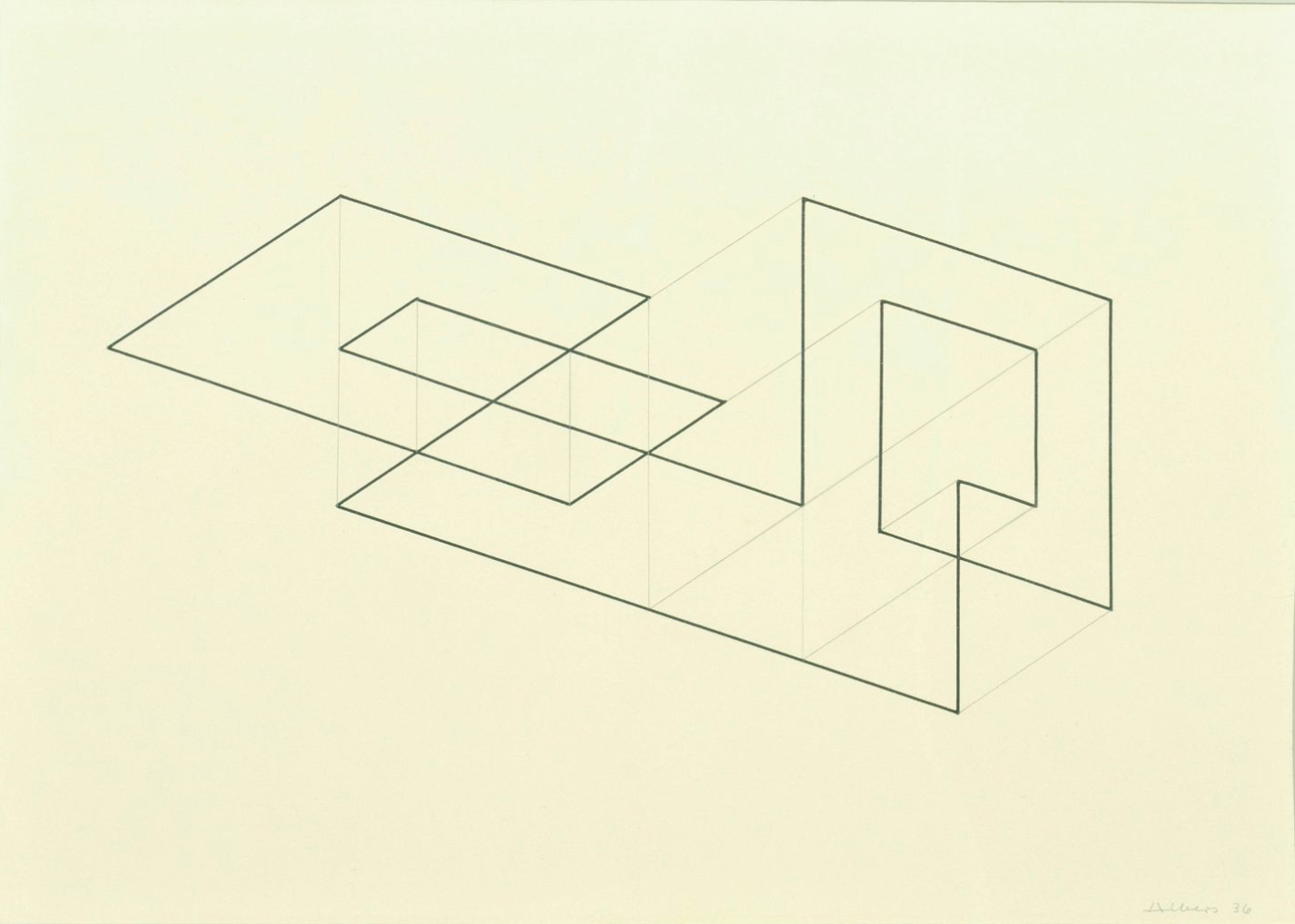

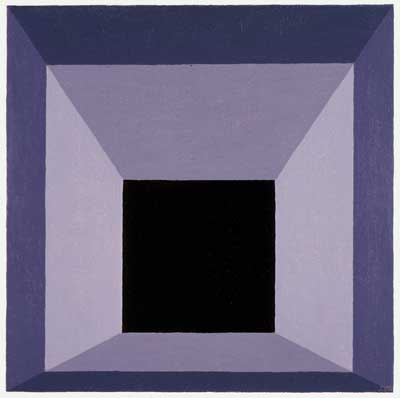

Josef Albers, Study for Tenayuca, 1936

Josef Albers, Study for Tenayuca, 1936A curation of works and pieces of music for SFMOMA’s Open Space Blog.

Resonance and illusion games: resonant frequencies of spaces, objects, and humans, and illusions that arise out of play.

In my own research, I try to find a disputable balance between scientific and subjective perception. I’m interested in the idea of learning as a beautiful physical experience or performance or even a game--creating a situation where individual perception of a piece can be as much a part of the process as the artist’s intent or an objective material-based truth.

Josef Albers stated this elegantly: “Experience teaches that in [visual] perception there is a discrepancy between fact and psychic effect.” I’d like to pair this with something of John Cage’s I read many years ago, where he talked about music as anything that improves audition (the process of hearing). To me, each of these statements poses a similar challenge--to create experiences that both trick and heighten our senses.

In the study of acoustics, every material or space has a set of resonances or frequencies at which it most easily vibrates. An opera singer’s high note shattering a glass may be an old wives’ tale, but the image is indelible. Sound becomes a new and heightened quantity, a visual and tactile event. In a film of a recent performance by the New Humans, a car resting on a sheet of glass is amplified and destroyed in the factory of its origin. Every strike of the sledgehammer and crack of glass is sonically fortified; the car sounds as though it is being dismantled by its own resonance.

To me, finding the resonant frequencies of an object or space is akin to creating a sound mirage of its dimensions. Auditory illusions also show us how we can perceive tonal information as something other than the sum of its parts. Illusions are, in general, experiences that arise out of bilateral symmetry (the fact that humans have a mirrored pair of almost everything—two ears, two eyes, etc) and the interactions or miscommunications that occur between halves. Our sense of spatiality and depth is entirely ruled by these pairs--finding our way in the dark, we calculate locations of obstacles by the different amounts of time the sound reflections take to reach each ear; when climbing a set of stairs the interactions between our eyes allow us to know the depth of the step we must take.

Many of the artists I have selected defy perceptual boundaries in some way, or use materials in a manner that demands a combined sense, or synaesthesia, of the perceiver. I tried to pick works that leap out of their medium or intended coordinates of perception: sculptures or spaces that beg to be sung into; paintings that shimmer or hover above canvas; bodies that just can’t seem to get comfortable; stereo-view photographs that coax our binocular vision into three dimensions. Then I paired them with musical compositions and practices that also ride along the boundaries of perception. Whether ‘playing’ scissors, or resonating the inner ear of the listener so that it actually begins to emit sound, these artists work in illusions.

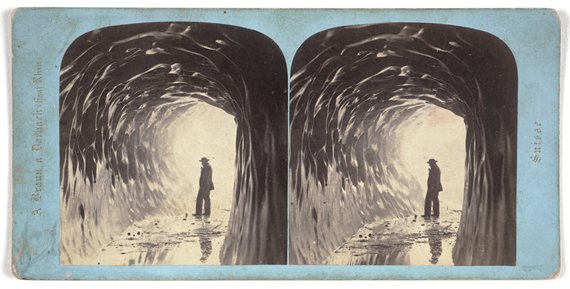

Adolphe Braun, Oberland Bernois, Switzerland, n.d.

“How May Your Parents and Your Employer Help You In Your Cricket Career?” Chris Corsano, The Young Cricketer, FamilyVineyard 2008

All the old albumen print photographs are incredible to me, simultaneously tactile and ephemeral—ah, to be made out of egg white, and salt, and silver, and sunlight! They remind me of a recent NY Times story about a newly blind painter who wanted to paint again so badly he learned to tell colours apart by the weight of the various pigments in his hands. Chris Corsano’s drumming reminds me of that kind of dedication to the transmutability of materials. Without any amplification, overdubs or effects he seems out to find the resonant frequency of every object he touches, listening as much as he performs. I’d love to hear what the inside of this cave sounds like….

Olafur Eliasson, Multiple grotto, 2004; © 2009 Olafur Eliasson

With Peruvian Scissor Dance (below). Clip courtesy The Seedling Project.

I still remember the physical weight on my eyes of the yellow light and purple after-images of Eliasson’s Room for one colour that was at SFMOMA last year, and I could not resist humming a few notes inside of Multiple grotto—it sounded marvelous in there! The video is of an Andean festival in 2006. Celebrations involve long stretches of counterpoint break-dancing accompanied by the percussion of broken scissor pieces played like castanets, and performers who “stick themselves with needles and cactus”; set off fireworks; and display snakes: ‘anything to make people gasp.’

Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Black Cañon, Colorado River, Looking Below, Near Camp 7, 18

Old timey “Holler/Ditty”, Leonard Emmanuel, from the compilation Hollerin’, Rounder Select 1983

“Hollerin’” is certainly music for the outdoors! This compilation of field and work hollers from North Carolina brings to mind a spot on the land where I grew up-if you stand on one end of the field and hoot at the right pitches, it somehow creates the most beautiful sort of standing wave and echo effects.

O’Sullivan’s almost iridescent print reminds me of Anthony McCall’s Solid Light films, where he documents the travels of light in various vapors and air densities. I’ve always wanted to create an auditory equivalent—instead of following trajectories of light, documenting sound in different temperatures and atmospheric hindrances. I used to live near a graveyard in Massachusetts, and I’ll never forget walking home one especially muggy night and noticing for the first time that the echo of passing cars was bouncing off of the headstones in a slightly different way than usual due to all the density of the moisture in the air!

Bruce Nauman, Wall-Floor Positions, 1968. © 2009 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Music of the Eskimo’s-Girl’s game, (Inuit folk song), Primitive Music of the World, compilation edited by Henry Cowell for Smithsonian Folkways, orig. release 1962

I love the rigorous game playing Nauman often does in his works. In this Sisyphean task he’s set for himself, the asymmetries of his body are amplified by the sheer angles of the architecture, and ironed out in attempts to span it, creating a situation where it’s easy to learn more about the body than the wall.

Here two young Inuit girls also play a game, a variant of traditional throat singing, using a metal pan as a resonator between them.

Harry Simmons, Signs of Three Crops, from the Nebraska Series, n.d. photo albumen stereo view

“Akazehe par deux jeune filles”, Burundi Musiques traditionelles, Ocora Records 1967

In another vocal game, this time from Burundi, two girls create a blended binaural illusion that makes it difficult to discern which tone is coming from which singer. The first time I heard it I had to be convinced it wasn’t just the kind of tape splices often found in musique concrete!

Anish Kapoor, Hole, 1988; © Anish Kapoor

“Ubuhuha”, Burundi Musique traditionelles, Ocora Records 1967

In the 19th century Alexander Melville Bell developed a revolutionary method for teaching the deaf to speak. Using what he called ‘visual speech’, (a written notation system that resembled and signified various anatomical parts of the vocal tract) he was able to teach even the profoundly deaf to make speech sounds that they had never heard. His son Alexander Graham and German physicist Herman Von Helmholtz also studied this phenomenon, further developing the idea of the vocal tract as a resonant cavity, and of vowels as tonal information (not unlike the rising and falling pitch of a bottle when filled with varying levels of liquid and blown across). An example from a Graham Bell lecture published in 1907 allows you to try this for yourself: Whisper the words eel, ill, ale, ell, and shall in succession, and listen to see if you hear a pitch either rising or falling. Not sure? Both Bells argued over this until they realized that this particular set of vowels is placed in the vocal tract like an hourglass and creates double resonances—if you listen carefully, the pitch is indeed both rising and falling!

In this sound clip a Burundian woman uses only her lips as a reed, altering the timber and spectrum of her voice by cupping her hands over her mouth in different shapes.

This piece by Anish Kapoor is almost more painting than object to me. I love the depth-saturated colour. And it reminds me of a beautiful-sounding, boot-shaped Martin Puryear sculpture a friend and I sung into at SFMOMA earlier this year.

Richard Boursnell and J. Evans Sterling, A Fancy Portrait of Number One Spirit, 1895

“Naduri”, (Georgian folk song), Drinking Horns & Gramophones 1902-1914 – The First Recordings In The Georgian Republic, Traditional Crossroads 2005

Georgian polyphony (“many voices”) predates much of western music, but has a unique ‘quintave’ tuning system. Quintave is based on the perfectly tuned fifth, but differs in that it includes a neutral third–one that is tuned sharp or flat, according to the particular melodic trajectory. Because of the neutral third, Georgian songs often end up higher than where they started! This work song of the Gurian tradition involves nonsense words to accommodate minute clashes of pitches as singers yodel and improvise over a structure of fifths. The result is terrifying and otherworldly to me. I think there’s an account in Herodotus of Georgians singing as they went into battle…

Tokujin Yoshioka, Honey-Pop Chair, 2001; © Tokujin Yoshioka

“Mantra”, Jean-François Laporte, Metamkine 2000

Laporte apparently used metal tubes etc as resonators for frequencies he wanted to emphasize, but other than that, this music is a one-take field recording of a cooling condenser for a hockey rink. It makes me think of other outrageous large scale machines or sounds I’ve been able to hear: a full-body scan for bone density sounded like harmonic rainbows, foghorns in San Francisco bay while camping out at Marin headlands made me feel as though my bones were disintegrating.

Yoshioka’s paper furniture is a gorgeous demonstration of a different kind of material resonance—here something soft and fragile is made strong through structural repetition, almost the reverse of the hulk of machined rhythms being teased into overtones and humming.

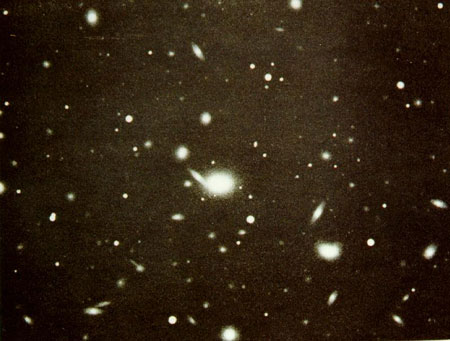

Vija Celmins; Untitled (Galaxy) from the portfolio Untitled, 1975; © Vija Celmins

“Avhinado”, Cantos de Aves do Brasil, gravados por Johan Dalgas Frisch, Sabia 1961

I’ve always been transfixed by Celmin’s work—how she manages to draw things with exacting detail that seem real but also hint at what we are not seeing when we photograph it—here the motion of light in a distant galaxy becomes kinetic and spatial in ink.

Bird calls often have such quick complex melodies that they blur the lines between sequential and spectral information—melody becomes vertical colour or timbre to the human ear. The complexity of this Avinhado bird call from Brasil astounds me by how synthesized it sounds. It’s humbling that an avian vocal tract can so effortlessly rival a whole generation of electronic sound discoveries.

Josef Albers, Homage to the Square, 1962. © 2009 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Bird and Person Dyning”, Alvin Lucier, Cramps Records, 1976

Alvin Lucier is one of the great pioneers of musically experienced phenomena. This piece, Bird and Person Dyning is a feedback-strand-laced document of ‘heterodyning’ or interactions of an electronic birdcall as simultaneously listened to and modulated by the composer/performer of the piece as they move around a space wearing binaural microphones. Bird holograms ensue! Lucier explains it really well here.

I’ve always loved it just as a piece of music, which is how I also feel about a lot of Alber’s work—each demonstration speaks for itself and holds as a beautiful if slightly strange event.

E.J. Woolsey, Specimens of Fancy Turning Executed on the Hand or Foot Lathe with Geometric, Oval, and Eccentric Chucks and Elliptical Cutting Frame, 1869

“Rumba”, Mildred Couper, Compositions of Mildred Couper 1887-1974, courtesy of Greta Couper c. 1990

Couper is a little-known 20th century composer who experimented with writing music for two pianos tuned a quarter-tone apart. “Rhumba” is a constantly down-spiraling tone, shedding layers as it goes. The closely tuned intervals cause phasing that sounds to me almost like the Doppler effect. As in in this line drawing by E. J. Woosley, these ‘fancy turns’ create a simple but rippling depth.

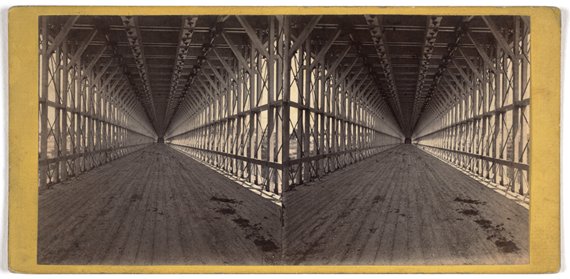

E. & H.T. Anthony & Co., Suspension Bridge Carriage Way, Perspective View, ca. 1890s

“Chorale 1", Maryanne Amacher, from Sound Characters: Making the Third Ear, on Tzadik 1999

Using closely mis-tuned musical intervals within a certain range of frequencies that are specific to the shape and curvature of the human skull, Amacher composes what she calls third ear music. In human auditory perception, these intervals (creating what are known in psychoacoustics as second-order beats) skitter back and forth between being interpreted as tonal and spatial information, causing the listener to feel like the tones are rotating around inside their own head. By manipulating oto-acoustic emissions (tiny frequencies that the ears emit even at rest) some of her pieces impel the inner ear to resonate and emit different sounds which also interact with the song. Despite the specificity of her compositions to anatomy, this is music for spaces and individual experimentation—best listened to loudly in a room (as opposed to on headphones) moving around, cupping your hands behind your ears etc: depending on where you are standing, the music undulates and changes.

—————-

Meara O’Reilly is a sound and visual artist living in Northern California, making instruments, songs, and performance installations based on the resonant frequencies of spaces, materials, and the human vocal tract. She is currently composing and filming a series of “chladni songs,” vocal music determined by resonances made visual in salt on a steel plate, as well as developing an album of songs based on auditory illusions found in folk music and psycho-acoustic research. http://www.myspace.com/mearabai